I just got to see Phou-oibi, the Rice Goddess, as part of the Tapestry of Sacred Music 2013 programme here at the Esplanade in Singapore. It is described as a Manipuri ballad opera, performed by the Laihui Ensemble from Manipur in North-East India.

It tells the story of a number of goddesses, including the Goddess of Fish, the Goddess of Water, the Goddess of Land, the Goddess of Metal, the Goddess of Wealth and the eponymous Goddess of Rice, Phou-oibi, who are sent by the Supreme God to the realm of humans, Lamlen Madam Madaima, to help them prosper. However, when they try to leave, they are stopped by the four protectors of the realm, under the orders of the Supreme God who believes that humanity will suffer once they leave. Phou-oibi, the Goddess of Rice, is the only one unable to escape - the stream she tries to cross turns into a huge river. Unable to cross the river, she meets a man, Akongjamba, who is out hunting. They meet and recognise instantly a connection they had in a past life. Akongjamba eventually proposes to Phou-oibi, who makes him wait till the full moon of the month of Sajibu to give her response. [Incidentally, we are currently in the month of Sajibu, which started last week with Sajibu Cheiraoba, the Meitei New Year.] However, at the appointed time, Akongjamba fails to show up. Enraged, Phou-oibi throws paddy down on the land.

According to the creative director, in other versions of the tale, the two end up together. In one version I just found in the book The Lois of Manipur: Andro, Khurkulm, Phayeng and Sekmai, Phou-oibi only spends a day in Akongjamba's house before she is forced to leave by his mother.

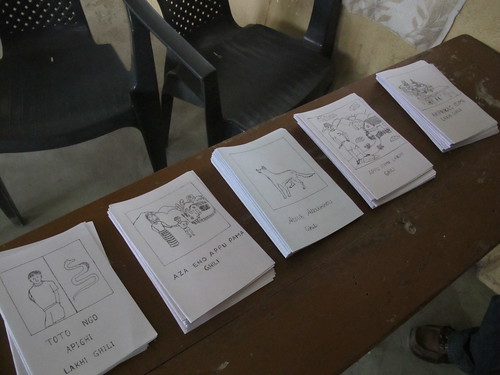

You can see short excerpts from the show here:

There are also videos of the performance on Youtube, though I'm not sure whether the uploader has the copyright.

I thought it was a wonderful production, from the performance to the lighting. The women, and especially the lead female, showed such control over their bodies and voices. I particularly enjoyed the flowing hand movements. I was also impressive by the physicality of a somersault that the women performed, given the limited movement afforded by their clothes and accessories (the wrapper around their waist, is what I think is called a phanek).

The post-performance talk / Q&A left a sour note in my mouth though. The very first question was, "Where are you from?", which I found to be incredibly offensive and disrespectful to the performers, given that the information was provided in the programme! As a follow-on question, I heard the same audience member make a comment that they didn't 'look Indian'. Surely, there are more culturally appropriate ways to ask someone about their place of origin. For instance, "I'm not familiar at all with Manipur, could you please tell me more it?" In contrast, asking "Where are you from?" basically implies, "The programme says you're from India, but where are you really from?" And of course, I get upset about these things because I have many friends from NE India who have to continually assert their membership as 'Indian citizens', both outside India and even when they live in other parts of India - though I do think / hope this is changing, with greater visibility by people like Mary Kom, a boxer from Manipur who won Bronze at last year's Summer Olympics.

But that aside, going back to what I loved about the show - what I loved most was, as stated in the programme, that the production was a collaboration between the various performers, musicians and artists and more importantly, that:

"Laihui Ensemble's The Rice Goddess gives free rein to its artists to improvise, and in doing so, allows them to reconstruct a traditional art form into a contemporary setting."

Culture and cultural performances are not static (unless we want them to be), and I think there's a lot to be said for finding the right balance between respecting tradition and producing work that a contemporary audience can still appreciate, even if it is a niche audience looking for something 'exotic'.

It tells the story of a number of goddesses, including the Goddess of Fish, the Goddess of Water, the Goddess of Land, the Goddess of Metal, the Goddess of Wealth and the eponymous Goddess of Rice, Phou-oibi, who are sent by the Supreme God to the realm of humans, Lamlen Madam Madaima, to help them prosper. However, when they try to leave, they are stopped by the four protectors of the realm, under the orders of the Supreme God who believes that humanity will suffer once they leave. Phou-oibi, the Goddess of Rice, is the only one unable to escape - the stream she tries to cross turns into a huge river. Unable to cross the river, she meets a man, Akongjamba, who is out hunting. They meet and recognise instantly a connection they had in a past life. Akongjamba eventually proposes to Phou-oibi, who makes him wait till the full moon of the month of Sajibu to give her response. [Incidentally, we are currently in the month of Sajibu, which started last week with Sajibu Cheiraoba, the Meitei New Year.] However, at the appointed time, Akongjamba fails to show up. Enraged, Phou-oibi throws paddy down on the land.

According to the creative director, in other versions of the tale, the two end up together. In one version I just found in the book The Lois of Manipur: Andro, Khurkulm, Phayeng and Sekmai, Phou-oibi only spends a day in Akongjamba's house before she is forced to leave by his mother.

You can see short excerpts from the show here:

There are also videos of the performance on Youtube, though I'm not sure whether the uploader has the copyright.

I thought it was a wonderful production, from the performance to the lighting. The women, and especially the lead female, showed such control over their bodies and voices. I particularly enjoyed the flowing hand movements. I was also impressive by the physicality of a somersault that the women performed, given the limited movement afforded by their clothes and accessories (the wrapper around their waist, is what I think is called a phanek).

The post-performance talk / Q&A left a sour note in my mouth though. The very first question was, "Where are you from?", which I found to be incredibly offensive and disrespectful to the performers, given that the information was provided in the programme! As a follow-on question, I heard the same audience member make a comment that they didn't 'look Indian'. Surely, there are more culturally appropriate ways to ask someone about their place of origin. For instance, "I'm not familiar at all with Manipur, could you please tell me more it?" In contrast, asking "Where are you from?" basically implies, "The programme says you're from India, but where are you really from?" And of course, I get upset about these things because I have many friends from NE India who have to continually assert their membership as 'Indian citizens', both outside India and even when they live in other parts of India - though I do think / hope this is changing, with greater visibility by people like Mary Kom, a boxer from Manipur who won Bronze at last year's Summer Olympics.

But that aside, going back to what I loved about the show - what I loved most was, as stated in the programme, that the production was a collaboration between the various performers, musicians and artists and more importantly, that:

"Laihui Ensemble's The Rice Goddess gives free rein to its artists to improvise, and in doing so, allows them to reconstruct a traditional art form into a contemporary setting."

Culture and cultural performances are not static (unless we want them to be), and I think there's a lot to be said for finding the right balance between respecting tradition and producing work that a contemporary audience can still appreciate, even if it is a niche audience looking for something 'exotic'.