I was in Zunheboto town all of last week for the

Ahuna /

Ahunah (post-harvest) festival, and to get some project work done. I'm still recovering from the trip back to Guwahati, but here's a quick recap of last week's events.

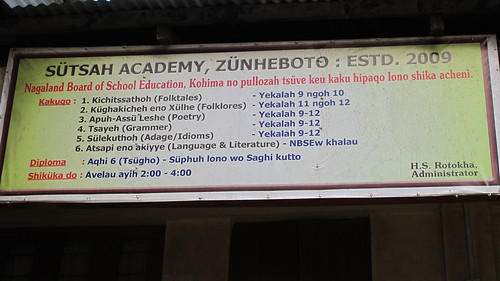

Monday night, we had the premiere of the film

The Silent Field, or

Yenguyelei Qha in Sumi. It's something that has come out of the cultural documentation project that Abokali and I have been working on the past 2 years with H.S. Rotokha and Pukhazhe Yepthomi. Most of the work on this film was done by Abokali and our wonderful video editor Vito Sumi (who had to work with most of our amateur footage), but I'll get to that in another blog post. Just to be clear, it's still a first edit that we were trying to rush for this year's Ahuna festival, but we hope people still enjoyed it.

From L to R: Me, H. S. Rotokha, Abokali Sumi, Pukhazhe Yepthomi.

Before I get into the cultural activities in my next post, I thought I'd just talk about the entrance to the festival ground.

The photos below [WARNING: some nudity] are of what I think was a modern take on an old tradition: the

genna post. The word

genna appears to come from the Angami

kenna, which according to Hutton, in his book

The Angami Nagas, translates as 'prohibition' (1921: 190), though the meaning of the term is quite broad and would deserve a blog post of its own. [Note that the Sumi equivalent is

chine, presumably related to the Angami word, but with the initial velar stop palatalisating before the front vowel /i/.]

The post was erected at the entrance to the local ground, with the words

sasüvi, meaning 'welcome' in Sumi.

On the right side, we see the chief guests for all the various events this Ahuna festival. Since every single event needs its own chief guest, a very important part of modern Naga culture.

And on the other side, we have pictures of the moon, sun, pieces of meat (steak actually), tiger, a pair of and a mithun head. Yes, disembodied breasts. I had to do a double take on that, especially given the highly conservative nature of Baptist Zunheboto.

I have no idea who commissioned the post, but it does bear the elements of a traditional Sumi

genna post. Of such posts, Hutton (in 1921) wrote:

Genna posts, whether the front centre post of the house

or the forked posts set up outside it, are carved both in high

relief and with incisions, the latter taking the form of

horizontal lines, crosses, circles, or arcs, and used to fill

in space not devoted to the serious carving, which generally

consists of mithan heads more or less conventionalised, and

highly conventional representations of the article of

ceremonial dress known as "enemies' teeth " (aghühu

). ... The only

living thing other than mithan which seems to be represented in Sema art is the bird, which is carved out of a

piece of wood and fixed to a crossbar between the "snail-horns" of the house. ... The sun and moon are

also represented, usually as plain circles or concave discs,

also breasts, singly, not in pairs, significant of success in

love, and wooden dao slings. -

The Sema Nagas (1921: 48)

I'm not sure if anyone was offended by them (I suspect some people might have been ), but as you can see, there was some cultural precedent for them, even badly photoshopped ones. Of course, it doesn't completely match Hutton's description, but I'm sure there were others types of

genna posts that he didn't get to document.

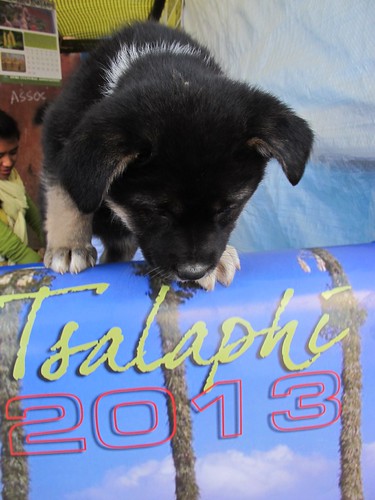

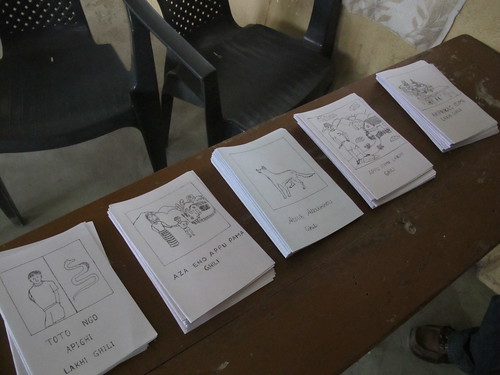

For most of the festival I was actually busy at the Sumi Cultural Association stall (since the members were busy with the main festival events.) We were selling DVDs of the film, as well as calendars for 2013.

The calendars (

tsalaphi) are unique in that they are completely in Sumi, with short explanations about the Sumi names for the various months. They are also accompanied by photos depicting the traditional agricultural activities / events typically associated with each particular month.

Here's our little (unofficial) calendar mascot. The girls helping us run the stall picked him up on the first day.

If you're interested in purchasing a calendar and live in Zunheboto, you can contact the Sumi Cultural Association in Zunheboto town. Alternatively, we will be trying to make them available in Dimapur, and also at the Hornbill Festival in Kohima. More information to come.